Earlier today we reviewed the Allansons / Mortgage Audit Services opportunity to invest in litigation funding.

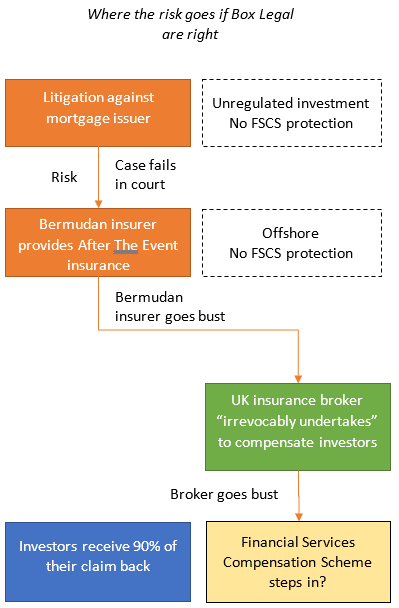

Allansons / MAS project a potential return of 50% should their cases succeed, and your money back if it fails via After The Event insurance – assuming that Leeward Insurance of Bermuda, the ATE insurer, agrees to pay the claim and has sufficient resources to do so.

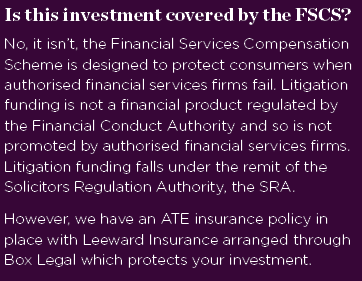

Allansons’ / MAS’ literature is clear that this investment is not covered by the Financial Services Compensation Scheme.

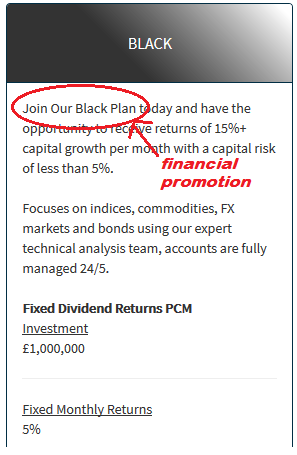

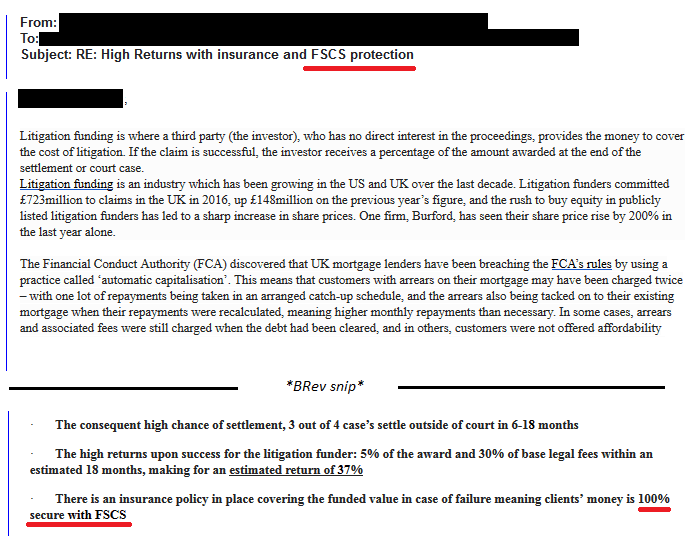

However, there are unregulated third party introducers promoting this investment as “High Returns with insurance and FSCS protection” and claiming that – via convoluted logic which we will review below – that the investment is covered by the FSCS, contrary to Allansons’ / MAS’ literature.

Allansons / Mortgage Audit Services cannot be held responsible for how unregulated third party introducers promote their investments, hence this point is being covered in a separate blog post to the opportunity itself.

The justification for the investment being promoted as FSCS-protected is shown above. This appears to be from a “terms & conditions” document but I have not had sight of the full document and do not know where it has come from beyond the unregulated introducer who emailed the above extract to a member of the public as part of their promotion.

The justification for the investment being promoted as FSCS-protected is shown above. This appears to be from a “terms & conditions” document but I have not had sight of the full document and do not know where it has come from beyond the unregulated introducer who emailed the above extract to a member of the public as part of their promotion.

In brief, what this extract says is that:

Box Legal has reviewed Leeward’s structure, finances etc, and will continue to do so, and has determined that there is no realistic prospect of Leeward failing to pay any claim.

Box Legal has reviewed Leeward’s structure, finances etc, and will continue to do so, and has determined that there is no realistic prospect of Leeward failing to pay any claim.- And that if Leeward fails to pay any claim, Box Legal “irrevocably accepts that it will have rendered negligent advice to the solicitor and thereby also to the Client, and agrees to be responsible to both the Solicitor and the relevant Client for all losses and claims arising out of that negligent advice”.

- And that as Box Legal is regulated by the FCA (not the Financial Services Authority – this was replaced by the FCA five years ago), its advice is covered by the FSCS.

This is a commendably imaginative way of attempting to provide FSCS cover for an investment offering potential returns of 50% over 6-18 months. However, it doesn’t work.

Essentially Box Legal claim that by inserting this clause about how they “irrevocably accept… to be responsible to both the Solicitor and the relevant Client for all losses and claims, including the non-payment of any valid claim” they have unilaterally shifted the risk from the investor onto the FSCS.

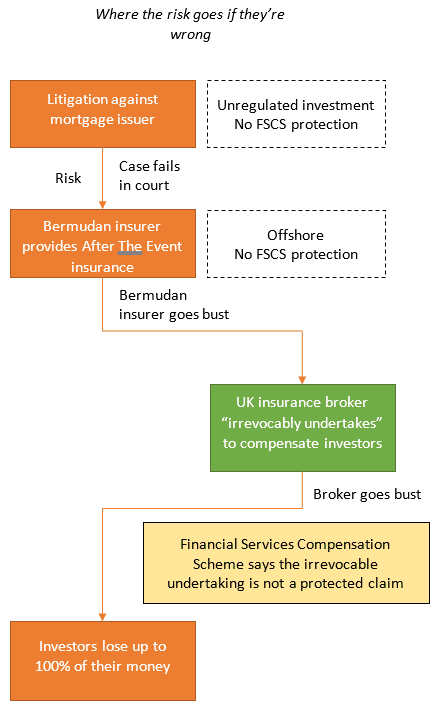

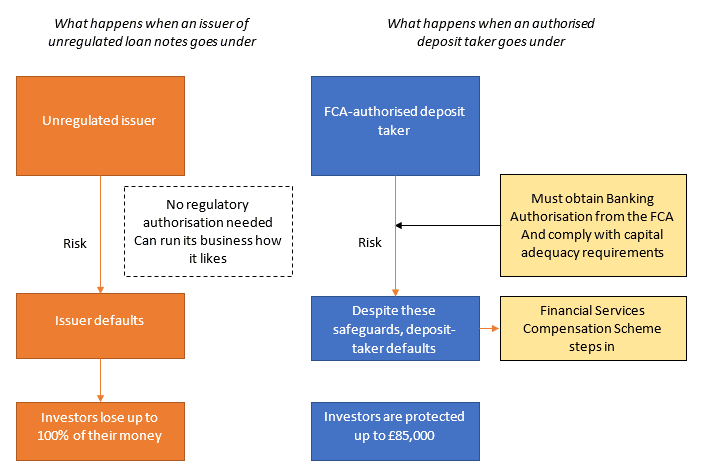

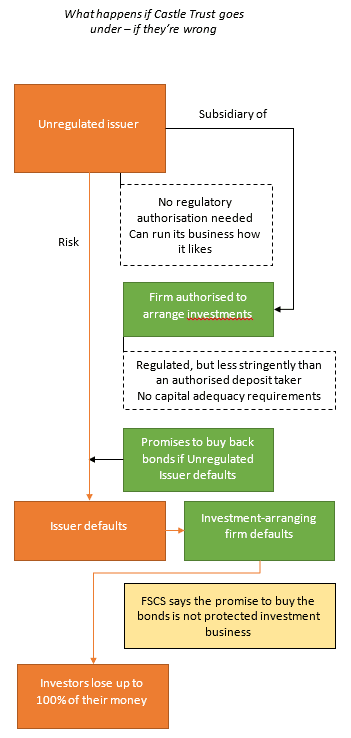

Unfortunately, it is not possible to dump liability on the FSCS by inserting clauses in contracts with words like “irrevocably accept”. Whether the FSCS is liable for a loss is governed by the definition of a “protected claim” found in the FCA’s COMP handbook.

If this approach worked, any financial adviser could write to their client saying that they “irrevocably accept that I will be liable if your investment goes down” and by doing so shift the investment risk from the client to the FSCS, while giving the client all the return if the investments go up. This would make them the most popular financial adviser in the country. But no adviser does. Why?

Box Legal would presumably say “because they weren’t clever enough to think of this”. The real reason is that saying “I irrevocably accept that I will be liable if your investments go down” or “I irrevocably accept that if this insurer goes bust I will be liable” and then failing to pay up is not a protected claim under the regulations governing the FSCS.

Advice is defined by the FCA as the provision of “personal recommendations to a client, either upon the client’s request or at the initiative of the firm, in respect of one or more transactions relating to designated investments”. The statement by Box Legal above is not a personal recommendation by any stretch of the imagination. Allansons / MAS investors are not all meeting with Box Legal to have a fact-finding exercise conducted and they are all being insured by the same insurer, so clearly Allansons / MAS investors are not all being provided with a personal recommendation to take out insurance with Leeward Insurance.

Advice is defined by the FCA as the provision of “personal recommendations to a client, either upon the client’s request or at the initiative of the firm, in respect of one or more transactions relating to designated investments”. The statement by Box Legal above is not a personal recommendation by any stretch of the imagination. Allansons / MAS investors are not all meeting with Box Legal to have a fact-finding exercise conducted and they are all being insured by the same insurer, so clearly Allansons / MAS investors are not all being provided with a personal recommendation to take out insurance with Leeward Insurance.

What Box Legal has done is broker the insurance contract, and insurance brokers are not automatically liable if their chosen insurer goes bust, any more than an investment adviser is liable if your investment falls.

Box Legal’s statement is in fact contradictory. The fact that they have “investigated and reviewed Leeward’s structure, management; claims payment record and finances…” means that even if Leeward fails, they will not have rendered negligent advice. Negligence would have occurred if Box Legal had brokered the insurance contract with any old insurer from a small island in the Atlantic and not paid any attention to that insurer’s capacity to pay. But Box Legal are specifically saying that they aren’t being negligent. If Leeward subsequently goes bust for reasons that Box Legal could not reasonably have foreseen when reviewing its structure and finances, Box Legal has not been negligent.

By irrecovably undertaking to recompense investors should Leeward Insurance fail, Box Legal may well be creating a legal obligation to do so that would stand up in a court of law. However, what it is not doing is creating a protected claim for the FSCS.

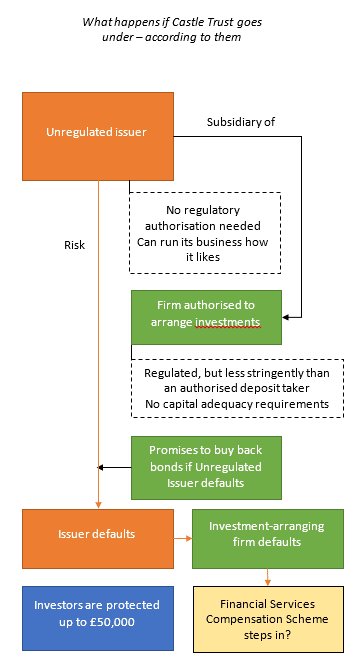

We do have to say that Box Legal’s claim is not a million miles away from the fact that people who are advised by an FCA-regulated adviser, who advises them to invest in unregulated investments, do get compensation from the FSCS when the investment goes bust and so does the adviser.

Same thing here, right? Regulated advice firm gives advice relating to unregulated investments, investments go bust, consumers must have their losses restored by regulated firm, regulated firm goes bust, FSCS must restore investors’ losses instead.

There are two problems with assuming the same will happen here. Firstly, advice to invest in unregulated investments is covered up to £50,000 only, so the FSCS’ liability is limited. Here, Box Legal are claiming that as insurance advice, investors are covered up to 90% of the claim, so the FSCS’ liability is virtually unlimited.

Secondly, as covered above, investors are not in reality being provided with personalised advice by Box Legal. Unlike in cases where a regulated adviser recommends that someone invests X amount of money in an unregulated investment, which is clearly personalised advice and is a protected claim.

(Note: the discrepancy between Box Legal’s claim that the FSCS will cover 90% of the investment and the unregulated introducer’s claim that clients’ money is “100% secure” is not explained. But frankly, if investors are only risking a 10% loss for investing in an unregulated product offering 50% returns over 6-18 months, who cares.)

This is our interpretation. Box Legal will no doubt disagree. Investors should bear in mind that the FSCS only decides whether a loss is a protected claim or not at the point a claim is made to the FSCS. By this time, it is too late for investors to back out. They should not expect the FSCS to state in advance whether they will be protected if the litigation funding investment goes south.

To the best of our knowledge, no company prior to Box Legal has attempted to secure FSCS compensation for an unregulated investment in this particular way, and had investors successfully claim losses from the FSCS. Equally, neither has any such claim failed. So Box Legal’s interpretation of the rules is untested, as is ours.

We will reiterate that these claims regarding Financial Services Compensation Scheme coverage were made by an unregulated introducer, who is also the source of the literature shown at the top of this article. They were not made by Allansons or Mortgage Audit Services Limited, who cannot be held responsible for how third party introducers describe their investment.

Allansons / Mortgage Audit Services states in their literature that this investment is not covered by the FSCS, and we agree with them.

Allansons / Mortgage Audit Services states in their literature that this investment is not covered by the FSCS, and we agree with them.

Should I invest with Allansons / Mortgage Audit Services litigation funding?

This blog does not provide financial advice. The following are statements of fact based on publicly available information, or near-universally accepted investment principles; they are not personalised recommendations. Investors should consult a regulated independent financial adviser if they are in any doubt.

As with any unregulated investment, there is potential for up to 100% capital loss should Allansons’ cases against mortgage lenders fail, Leeward Insurance fails to pay out, and the FSCS refuses to consider Box Legal’s “irrevocable undertaking” as a protected claim.

Unregulated investments with potential for 100% capital loss are only suitable for sophisticated and/or high net worth investors who have a substantial existing portfolio.

If you are looking for an investment that provides “100% security” or FSCS protection, you should not rely on novel and untested interpretations of the FSCS compensation rules, and you should not invest in unregulated products with a risk of 100% capital loss.

Footnote

Box Legal has been in business for nearly 15 years according to Companies House.

In the last accounts (to 31 August 2016) the auditors (UHY Hacker Young) stated:

Emphasis of matter – Going Concern

In forming our opinion on the financial statements, which is not modified in this respect, we have considered the adequacy of the disclosure made in accounting policy 1.2 to the financial statements concerning the company’s ability to continue as a going concern. The company has fallen short of certain regulatory requirements relating to compliance with the FCA rulebook during the year and as at the year end date. Whilst the implications of these instances of non-compliance are uncertain the directors believe they will be resolved without financial impact and have therefore continued to adopt the going concern basis in the preparation of the financial statements.

These conditions indicate the existence of a material uncertainty which if resolved unfavourably (despite the Directors view that this is unlikely to be the case) have the potential to cast significant doubt over the company’s ability to continue as a going concern.

It should be noted that many financial firms fall foul of the FCA rulebook with no lasting consequences. In a later note Box Legal’s failure to comply with regulatory requirements is described as relating to “holding client money and other areas of compliance”. This may well result in nothing more than a fine and/or an instruction from the FCA to improve their client money procedures. In general, we have no reason to doubt the directors’ belief that there will be no financial impact.

However, given that unsophisticated consumers are being told that this investment is “100% secure with FSCS”, which rests on Box Legal’s novel and untested interpretation of FSCS compensation rules, which is part of the FCA rulebook, investors should be aware that Box Legal has previously been tripped up by other parts of that rulebook.

Under the

Under the  Braxton Knight’s FAQ refers to “our dedicated financial advice” and states “We offer completely independent advice.”

Braxton Knight’s FAQ refers to “our dedicated financial advice” and states “We offer completely independent advice.”

The justification for the investment being promoted as FSCS-protected is shown above. This appears to be from a “terms & conditions” document but I have not had sight of the full document and do not know where it has come from beyond the unregulated introducer who emailed the above extract to a member of the public as part of their promotion.

The justification for the investment being promoted as FSCS-protected is shown above. This appears to be from a “terms & conditions” document but I have not had sight of the full document and do not know where it has come from beyond the unregulated introducer who emailed the above extract to a member of the public as part of their promotion. Box Legal has reviewed Leeward’s structure, finances etc, and will continue to do so, and has determined that there is no realistic prospect of Leeward failing to pay any claim.

Box Legal has reviewed Leeward’s structure, finances etc, and will continue to do so, and has determined that there is no realistic prospect of Leeward failing to pay any claim. Advice is defined by the FCA as the provision of “personal recommendations to a client, either upon the client’s request or at the initiative of the firm, in respect of one or more transactions relating to designated investments”. The statement by Box Legal above is not a personal recommendation by any stretch of the imagination. Allansons / MAS investors are not all meeting with Box Legal to have a fact-finding exercise conducted and they are all being insured by the same insurer, so clearly Allansons / MAS investors are not all being provided with a personal recommendation to take out insurance with Leeward Insurance.

Advice is defined by the FCA as the provision of “personal recommendations to a client, either upon the client’s request or at the initiative of the firm, in respect of one or more transactions relating to designated investments”. The statement by Box Legal above is not a personal recommendation by any stretch of the imagination. Allansons / MAS investors are not all meeting with Box Legal to have a fact-finding exercise conducted and they are all being insured by the same insurer, so clearly Allansons / MAS investors are not all being provided with a personal recommendation to take out insurance with Leeward Insurance. Allansons / Mortgage Audit Services states in their literature that this investment is not covered by the FSCS, and we agree with them.

Allansons / Mortgage Audit Services states in their literature that this investment is not covered by the FSCS, and we agree with them.

Allansons claims to have been established in 1993. Allansons LLP was only incorporated with Companies House in 2008, but this is explained on Allanson’s website which states that the business was originally a sole practitioner, went on to purchase several other solicitors and converted to a limited liability partnership in 2008.

Allansons claims to have been established in 1993. Allansons LLP was only incorporated with Companies House in 2008, but this is explained on Allanson’s website which states that the business was originally a sole practitioner, went on to purchase several other solicitors and converted to a limited liability partnership in 2008.

If it is possible to obtain FSCS cover in this way, why doesn’t every bond issuer set up an FCA-regulated company, have it promise to buy their bonds in the event of default, and by doing so, substantially lower the coupon it will have to pay to attract investors?

If it is possible to obtain FSCS cover in this way, why doesn’t every bond issuer set up an FCA-regulated company, have it promise to buy their bonds in the event of default, and by doing so, substantially lower the coupon it will have to pay to attract investors?

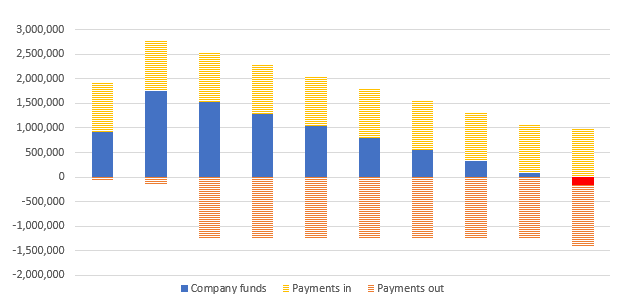

The 2016 collapse was widely covered in the media; Deloitte’s subsequent picking over the bones has received little press coverage. This is not that surprising as “Investors in scheme that collapsed in 2016 have still lost their money” is not news.

The 2016 collapse was widely covered in the media; Deloitte’s subsequent picking over the bones has received little press coverage. This is not that surprising as “Investors in scheme that collapsed in 2016 have still lost their money” is not news.